What happens when a weak real estate market and under-regulated rental housing collide on the streets of Jamestown? People get trapped.

Consider the recent case of a 71-year-old woman on Bush Street profiled by The Post-Journal. Her apartment was without hot water or heat for almost a week when a broken pipe flooded her basement. Her Florida-based landlords and their locally-based maintenance crew were unresponsive. She was trapped in a cold apartment during the coldest month by a landlord who shouldn’t have been operating in Jamestown.

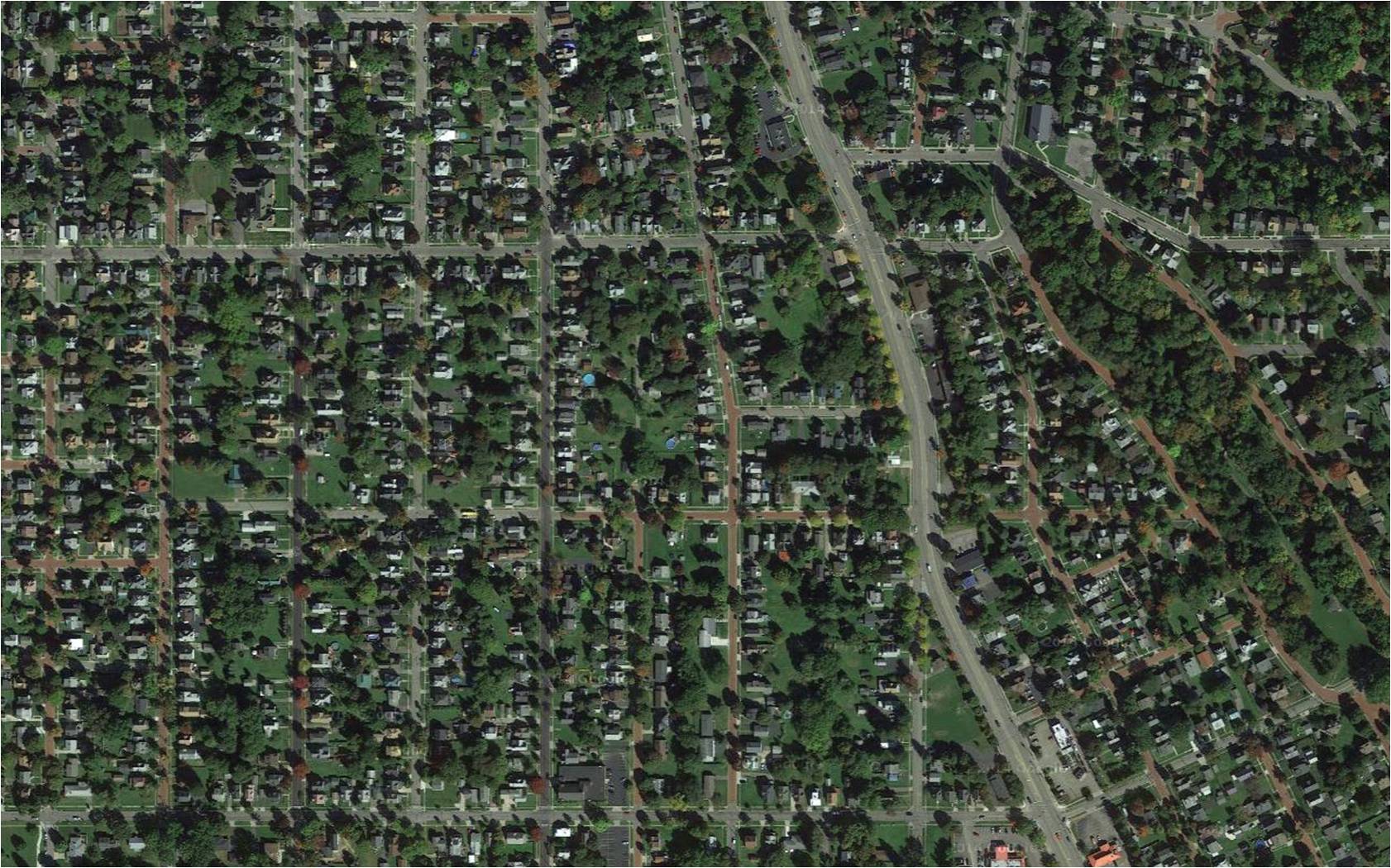

Or consider the cases of hundreds of Jamestown homeowners who live near poorly maintained and poorly managed rental properties. Their quality of life is less than it should be and so is the market value of their homes. When it comes time to sell, they know it’ll take a while to find a buyer and they’re bound to take a financial hit. They feel trapped in declining neighborhoods.

How about the city’s accidental landlords? They’re trapped too. These are folks who inherit a house and have a hard time selling it, or people who moved out of the area for a job and have been unable to find a suitable buyer. They rent the property to pay their bills. Their intentions are good and they try their best, but they’re trapped in a business they didn’t choose.

The city’s good landlords – who outnumber the bad ones – are caught in multiple traps. They chose this business and they take it seriously. They monitor, maintain, and reinvest in their properties to protect their assets. They screen for good tenants and are responsive to neighbors. But their business and their image is undermined by bad landlords whose shoddy practices keep rents artificially low, thus undermining efforts by good landlords to maintain a quality product. The market is signaling them to lower their standards and be less responsible, or surrender their profitability.

All of these traps are symptoms of a market that simply doesn’t work for the vast majority of Jamestowners – homeowners, tenants, and landlords. They’re the drivers of disinvestment, deferred maintenance, and absenteeism. They lead to lower property values, higher tax rates, and a pervasive sense of helplessness.

The market needs correcting through multiple, coordinated strategies, many of which are well under way. To rightsize the supply side of the equation, an aggressive demolition campaign by the City of Jamestown and Chautauqua County Land Bank will tear down as many as 60 houses by the end of 2016, chipping away at a glut of obsolete, derelict units.

On the demand side, efforts to boost neighborhood desirability through pride and collective reinvestment are ongoing through the JRC’s Renaissance Block and GROW Jamestown programs. Code enforcement sweeps, tree planting, and infrastructure by the city are also making headway on this front.

But a big piece of this overall effort to correct a broken market is missing: stronger regulation of the rental housing market.

In its current under-regulated state, bad landlords are able to operate alongside the good. Rather than proactively monitoring these properties to ensure that they’re properly maintained, the city relies on a longstanding reactive approach that’s more suited to a healthier, functional housing market.

What’s needed is a system of registration and licensing to ensure that all rental units meet basic standards of safety and maintenance. If a rental property doesn’t pass inspection, it doesn’t get a license. Without a license, it can’t be rented. Without rental income, the owner is forced to make a choice: correct the problems or move on.

Over time, adopting a more proactive approach has several positive effects. Bad landlords stay away from the market and prey instead on communities where their neglect has fewer consequences. As this happens, good landlords are no longer forced to compete on an un-level playing field. The race to the bottom ends, the market stabilizes, and investment is more likely to be rewarded. And then, one by one, those caught in the traps laid by a dysfunctional market are released.

Does this transition cause disruption? Of course. Many of the worst rental properties would be forced to close because the needed repairs would be cost prohibitive. But if efforts are made to steer these properties into a demolition or rehabilitation pipeline, while finding suitable housing for any displaced residents, this disruption can be part of the foundation of a market rebound.

The JRC and some its neighborhood partners have worked over the past few years to research regulatory approaches used in cities that have dealt with similar traps. Visit Policy Research at JamestownRenaissance.org to learn more about our work on this topic and to offer your perspective on ways to improve Jamestown’s housing market.

— Peter Lombardi

This post originally appeared in The Post-Journal on March 9, 2015, as the JRC’s biweekly Renaissance Reflections feature.